Skin in the Game: Litigating High-Stakes Matters on Contingency

“If you’re paid before you walk on the court, what’s the point in playing as if your life depended on it?”

“If you’re paid before you walk on the court, what’s the point in playing as if your life depended on it?”

Arthur Ashe

I. Skin in the game of high-stakes litigation.

“Skin in the game” means exposing yourself to the consequences of your actions—having a personal stake in the outcome.

In the world of high-stakes business litigation, most law firms do not have real skin in the game. These firms bill by the hour. They get paid millions in legal fees whether their client wins or loses. And they do not put their own money on the line. These firms are incentivized to bill hours.

But a few rare business litigation firms do have real skin in this game. These firms work on full contingency for a percentage of the return. They risk millions of their own capital to fund litigation costs and only get paid if their clients win. These firms are incentivized to win.

Hiring a contingency fee law firm to litigate high-stakes cases eliminates the downside risk of paying millions in attorneys’ fees and litigation costs if the case is not successful. However, eliminating this downside risk is just one benefit of a contingent fee structure. There are less obvious, but equally important, benefits of hiring a law firm with real skin in the game.

We start by explaining how a contingency fee arrangement eliminates the client’s downside risk. We then explore the more significant benefits of a contingency fee structure: aligning the law firm’s incentives with the client’s goals and achieving extraordinary results.

II. A contingency fee structure eliminates the downside risk to the client of millions in legal fees and costs.

Imagine you have an extraordinary opportunity to invest in a company that is performing clinical trials for a new drug. You can borrow money to invest in the company. If the clinical trials are successful and the investment does well, you share in the gains, including any unexpectedly high gains. But if the clinical trials are not successful and the investment fails, your loan is forgiven—the downside risk to you is zero.

Imagine you have an extraordinary opportunity to invest in a company that is performing clinical trials for a new drug. You can borrow money to invest in the company. If the clinical trials are successful and the investment does well, you share in the gains, including any unexpectedly high gains. But if the clinical trials are not successful and the investment fails, your loan is forgiven—the downside risk to you is zero.

This investment is too good to be true. But for a client with a high-stakes legal matter, this investment opportunity parallels a contingency fee arrangement.

In effect, the contingency fee firm provides a risk-free loan to finance the client’s litigation—a loan that will only be repaid if the firm is successful. “[T]his fee arrangement provides clients with credit (since the fee is paid only on recovery) and with a sort of insurance (since the fee is not paid if the claim fails) that is not available to the client in an hourly fee contract.” 1

If, using a contingency fee structure, the risk of attorneys’ fees and costs in the event of a loss simply vanished, this would eliminate the client’s exposure to tens of millions in fees and costs. 2 But using a contingency fee structure, the risk of fees and costs do not simply vanish. Instead, “[t]he contingency fee arrangement shifts substantial risk of costs and loss to the attorney.” 3

Offloading this risk from the client to the law firm results in a law firm with real skin in the game. The firm faces real consequences if it does not win—and win big. As explained below, this shifted risk produces dramatic benefits to the client.

III. Skin in the game aligns the law firm’s incentives with the client’s goals.

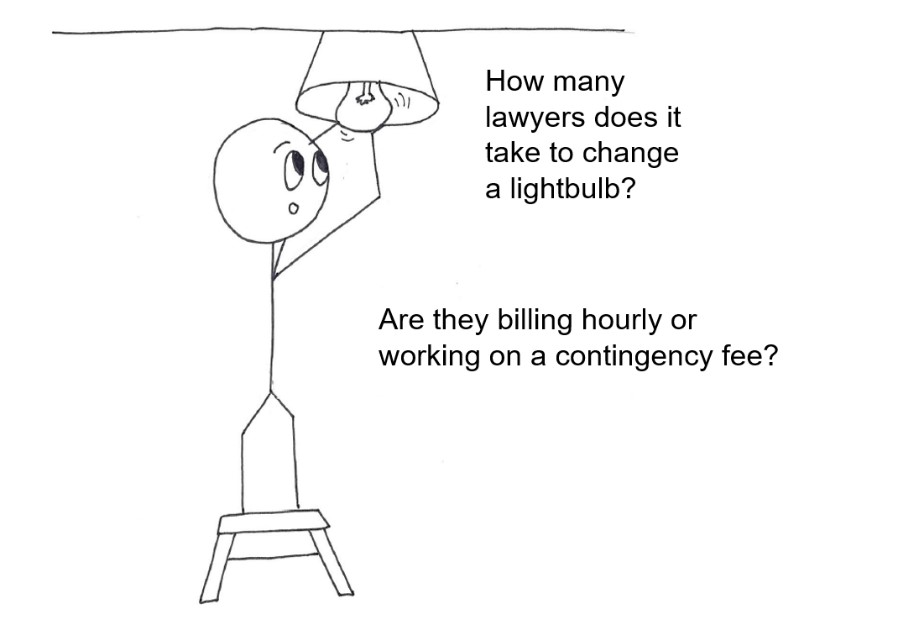

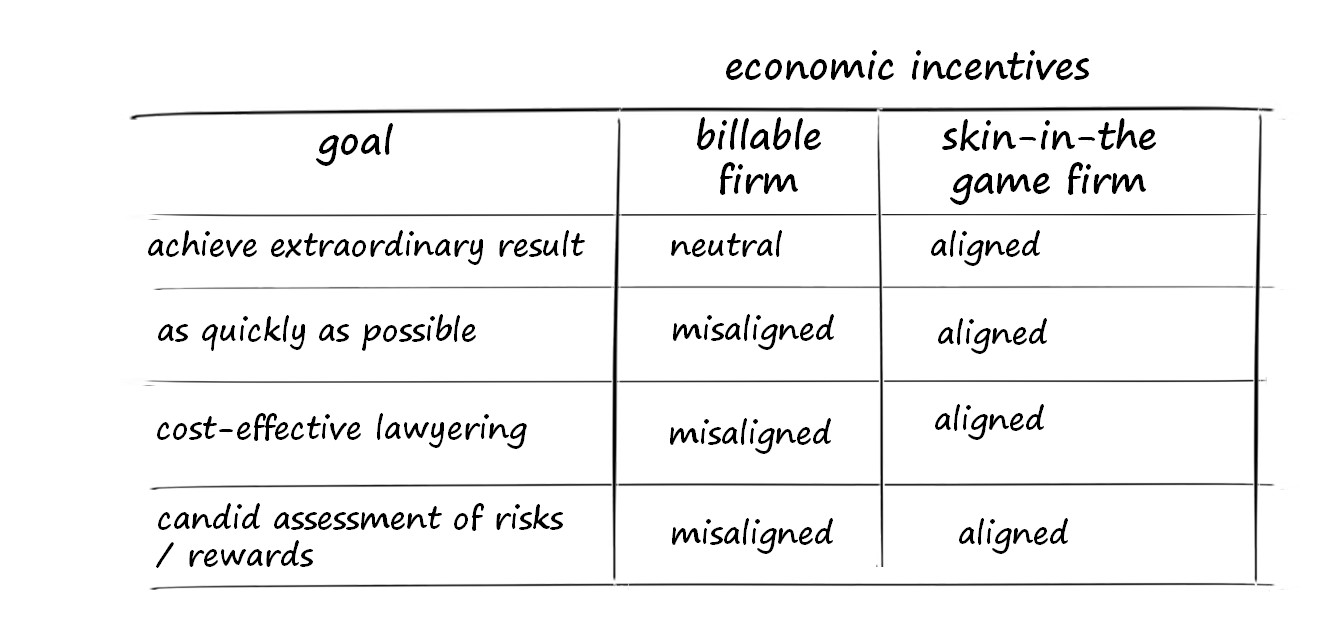

In high-value business litigation, a plaintiff client has four primary goals: (1) achieve an extraordinary result, i.e., the greatest recovery; (2) as quickly as possible; (3) at a cost-effective price; and (4) receive candid assessments of the case from its lawyers, both before the case is filed and throughout the life of the case. 4

The economic incentives for firms that bill by the hour are often directly at odds with these client goals. 5

Conversely, the economic incentives of a contingency fee law firm, with real skin in the game, are aligned with the client’s goals.

Let’s explore each goal.

Goal 1: extraordinary results.

1. billable hour firm.

The direct economic incentives of the billable hour firm are indifferent to the outcome of a case. Whether the firm achieves an extraordinary, good, mediocre, or even poor result, the firm is paid the same. “With hourly fees, the plaintiff’s lawyer loses any direct financial interest in the outcome of the case.” 6

While hourly billers have indirect benefits associated with achieving an extraordinary result (e.g., personal satisfaction, enhanced reputation, etc.), they receive the same fees independent of the result they obtain, even if that result is a total loss for the client.

2. contingency fee firm.

Under a contingency fee structure, the firm’s economic incentives are directly tied to the client’s goal—the greater the client’s recovery, the more the law firm makes. The law firm is incentivized to achieve not just a win but an extraordinary win. “[T]he attorney and client interests are highly aligned. The attorney has an incentive to maximize the plaintiff’s litigation return.” 7

Goal 2: as quickly as possible.

1. billable hour firm.

Hourly fee lawyers have a direct economic incentive to extend the duration of a case as long as possible and delay settlement, independent of whether doing so increases or decreases the case’s expected value. 8 The longer a case drags on, the more time is available to bill hours.

This incentive translates into real-world effects. Empirical studies demonstrate that “hourly fees … increase the time to settlement.” 9

2. contingency fee firm.

With a properly structured contingency fee arrangement, the quicker the law firm can secure an extraordinary recovery, the better for both the client and firm.

A quicker result allows the client to invest the recovered capital sooner rather than later. For some clients, delaying a high-value recovery can have a profound impact on the client’s financials or even the ability of the client to continue as a going concern. In addition, a quicker result reduces the time during which the client and its employees are distracted by the litigation.

The contingency fee law firm has similar incentives to resolve a case quickly. A quicker recovery allows the firm to recoup its investment and re-invest its share of the recovery sooner rather than later. It also frees up the firm’s resources to invest in other opportunities.

Goal 3: at a cost-efficient price.

Cost-efficient lawyering means that the law firm only charges its client fees when those fees are likely to increase the recovery for the client by an amount that is that greater than those fees, i.e., that the fees are justified by a likely return on investment.

Cost-efficient lawyering does not mean the cheapest price. Rather, cost-efficient means that the expected value of the client’s recovery resulting from incurring the legal fees is greater than zero—hopefully significantly greater than zero. A client would prefer that a law firm charge more fees if incurring those additional fees directly results in an increase in the client’s return net of those fees.

1. billable hour firm.

The client’s goal of hiring a cost-efficient law firm is at odds with the direct economic incentives of a firm that bills its hours.

The client wants the firm to bill as few hours as necessary to achieve the optimum result. Billable firms, however, make more money with every hour billed, resulting in an economic incentive to bill as many hours as possible, independent of how those billable hours affect the case’s expected value and net return to the client. “Because the attorney will bill the client solely on the basis of the number of hours worked, regardless of the result for the client, it is in the economic interest of the attorney to work as many hours as possible on each case.” 10

Inefficiency—such as duplicating legal research, reinventing the wheel, filing unnecessary motions, having multiple attorneys attend the same depositions and hearings, etc.— “rewards an inefficient attorney with more billable hours and thus more income.” 11 “[H]ourly billing increasingly has been assailed for encouraging inefficiency…hourly billing diminishes incentives for expeditious work.” 12 And more billable hours—i.e., more inefficiency—means that more money is transferred from the client to the law firm.

Complicating this misalignment is the fact that some clients may not have the information and knowledge necessary to determine what is actually needed to maximize the value of the case. For these clients, “[o]nly the attorney knows whether a case needs additional work or not. … The plaintiff is forced to rely on the attorney’s recommendation.” 13

Even if a client did have such information and knowledge, there is often no effective way for the client to monitor the billable firm’s work to ensure that the hours billed are efficiently designed to maximize the case value. Many clients are not in a position to monitor the efficiency of undertaking a particular task—its cost relative to the impact on the case’s expected value. And billable firms, with no conscious ill intent, still respond to their direct economic incentives and undertake tasks that would not be worth doing based on a cost / benefit analysis.

“[I]ncentives that organizations develop—intentionally (through policies and procedures) or inadvertently (through the unintended consequences of those policies and procedures)—have profound effects on behavior.” 14 As a result, decisions about what tasks to focus on, how many lawyers should work on those tasks, which lawyers are assigned to the tasks, and how much time should be spent on those tasks are driven by “reasons other than expertise and efficiency.” 15 Moreover, the compensation for individual attorneys increases with increased hours billed. 16

The lack of economic incentives for a billable firm to work efficiently creates a conflict between the clients and their attorneys, that often results in billing disputes. 17 Researchers have described this misalignment as a perverse asymmetry: “With hourly fees …the lawyer and the client now have opposing interests in the amount of time the lawyer spends working on the case—the longer the former works the more she earns, and the more the latter pays.” 18 The cost associated with inefficiency is shouldered entirely by the client, while the law firm benefits from inefficiency. 19 To be sure, most hourly billing law firms are ethical, have no malicious intent, and would not intentionally overbill a client, e.g., pad bills to include work that was not actually performed or artificially increase the amount of time billed for projects. But economic incentives influence behavior. Billable law firms are not incentivized to provide cost-efficient lawyering—they are incentivized to provide cost-inefficient pricing.

2. contingency fee firm.

A contingency fee firm cannot run up its fees by spending time on tasks that do not increase the client’s net recovery. If the contingency fee firm’s fee percentage is, for example, 30% of the net recovery, the number of hours that the firm spends on the matter is irrelevant to the fee—only the amount of the recovery achieved by the law firm determines how much the firm is paid.

With a properly structured contingency fee agreement, the law firm’s economic incentives are aligned with the client’s goal of securing an optimum result as efficiently as possible. “They, like the client, are motivated by the outcome and quality of the case to work efficiently and to build an excellent case.” 20 Having real skin in the game incentivizes the contingent law firm to litigate as efficiently as possible. “If the client cannot observe (or cannot contract upon) his attorney’s effort, then linking the attorney’s fees to the trial’s outcome [with a contingency fee structure] induces the attorney to exert a higher, more efficient level of effort than could be implemented using hourly or fixed fees.” 21 Through the contingency fee structure, attorneys and plaintiffs “address a moral hazard problem: if the client cannot observe the attorney’s effort, then tying the attorney’s fees to the trial’s outcome provides better incentives to exert efficient effort than hourly fees.” 22

Moreover, having real skin in the game incentivizes the contingent law firm to efficiently focus on adding real value that impacts winning versus losing rather than what simply provides opportunities to bill. “As one author has aptly noted, ‘1,000 plodding hours may be far less productive than one imaginative, brilliant hour.’” 23 Straight hourly billing has no way of capturing the value to the client of that ‘one imaginative, brilliant hour.’” When a contingency fee firm litigates a case efficiently and, as a result of its efforts, achieves an extraordinary recovery, its total fee may end up being higher than the fee that a billable firm might have charged. This is not cost-inefficiency. When this situation occurs, the contingency fee is usually higher because the recovery itself is greater than the recovery that a billable law firm (with the misaligned incentives) would have achieved.

3. an illustrative example.

Litigating a high-value dispute involves hundreds of individual decisions. Some decisions are major: should the client mediate; should the client waive jury; who should be called as trial witnesses; etc. Other decisions are minor: should the law firm bring a motion to compel the other side to produce additional documents related to a tangential issue; should the client request an extension to file an opposition to a summary judgment motion; etc. For each decision, the contingency fee firm’s economic incentives are aligned with the client’s goals—what course of action will achieve the optimum result for the client as efficiently as possible. The billable firm’s economic incentives are at odds with the client’s goals.

Consider the following concrete example involving a relatively minor decision: should the plaintiff bring a discovery motion to compel the defendant to produce documents relating to a tangentially related transaction?

For the client, the benefit of bringing this motion is negligible—a chance of obtaining documents that have less than a .01% chance of actually being used at trial. Countering this negligible benefit is the distraction cost associated with diverting the firm’s focus from end-game critical issues and, if the firm is billing, a cost of $55,000. With perfect information, the expected value of the motion to the client (even without the attorneys’ fees) is either zero or possibly negative. The client would never want its law firm to bring this motion.

The contingency firm would not bring this motion—it would not waste resources on a distracting motion with a negative expected value rather than focusing on, and adding value to, the end game. The billing firm would likely bring this motion. The motion would result $55,000 in easy billing by leveraged associates and does not require the gumption needed to address the key challenging problems in the case. “Hourly billing also has been blamed in part for the continued proliferation of burdensome and often unnecessary discovery in civil litigation.” 24

Odds are that the billable firm would not ask the client whether the firm should bring this discovery motion. And if the client did ask the law firm about the motion and received advice from the firm, that advice is coming from someone who can only gain from bringing the motion without any downside consequences.

“It is hard to image a more stupid or more dangerous way of making decisions than by putting those decisions in the hands of people who pay no price for being wrong.”

Thomas Sowell

Each case involves hundreds of decisions. The costs and consequences of each of these decisions add up. Should these decisions be made by a firm that has incentives aligned with or at odds with the client’s goals?

Goal 4: candid counseling.

“Beware of the person who gives advice, telling you that a certain action on your part is “good for you” while it is also good for him, while the harm to you doesn’t directly affect him.”

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life

1. billable hour firm.

The client’s goal of receiving candid advice regarding whether to file, settle, or continue to pursue litigation, and the economic incentives of a billable firm are, once again, at odds.

The billable firm’s economic incentive is to bill hours, which requires filing and litigating cases. Cases include both those that should be filed and those that should not, either because the client’s expected value (recovery minus costs) is less than zero or because doing so would otherwise not be in the client’s best interest.

When a billable firm evaluates a case, the firm’s economic incentive is to overvalue the case’s upside and undervalue the risk, budget, and client’s investment of time. 25 This incentive is particularly troubling where there is asymmetric information and knowledge between the law firm and the client regarding how the litigation may play out. As a result, the billable firm’s economic incentive encourages filing lawsuits that, from the client’s perspective, should not be filed. 26

In addition, the billable firm has direct economic incentives to continue to litigate cases and bill hours, even for those cases that should be settled. Some cases that perhaps should have been filed based on the limited information known at the time of filing may take a dramatic turn for the worse. At that point, the client’s best interest is to resolve the case and stop the bleeding. For other cases, the defendants could offer significant money to settle the case, well above the case’s true expected value.

But if these cases are resolved, then the billable monthly income stream disappears. As a result, the billable firm’s economic incentive is to overvalue the case, minimize or sugar coat its problems, and continue billing.

2. contingency fee firm.

Having real skin in the game incentivizes a contingency fee law firm to accurately assess a case’s value and be candid with the client.

If a case should not be filed—e.g., if the case has fatal problems that cannot be fixed even with exceptional lawyering—the contingent firm’s incentives are to tell the client the hard truth. Contingency fee firms “have incentives to proceed only with cases that [have] merits.” 27

In addition, a contingency fee firm with aligned incentives encourages candid counseling during the course of the litigation, including whether or not to accept an offer to settle the case.

Summary of goals / economic incentives

IV. Skin in the game creates the gumption necessary for the law firm to consistently achieve extraordinary results.

“Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.”

Charles Munger

A. Upside incentives produce superior results.

Consider two identical companies with two CEOs. Each CEO is essentially the same—the same education, experience, and skill set. But their compensation structure is very different.

One CEO receives an annual base salary of $5 million and a $20 million bonus, independent of how the company performs. There is no incentive plan. If the company does well, she gets her $20 million bonus; if the company does poorly, she gets her $20 million bonus. This CEO has minimal skin in the game.

The other CEO has a “pay-for-performance” incentive structure that aligns her compensation with the company’s success. She also has a $5 million base salary. But rather than a fixed bonus, she has an incentive plan that includes stock options and target milestones based on the company’s performance. If the company does poorly, her bonus is $0; if the company performs well, her bonus could be $20 million; and if the company exceeds expectations, her bonus could exceed $50 million. This CEO’s fortune rises and falls with the company’s performance. This CEO has skin in the game.

Which CEO would you bet on to succeed? Studies prove that companies that significantly motivate their CEOs with economic incentives outperform those with no (or low) economic incentives. 28 Incentivized CEOs have the gumption, drive, and creativity to ensure that their companies not only hit their milestones but achieve extraordinary results.

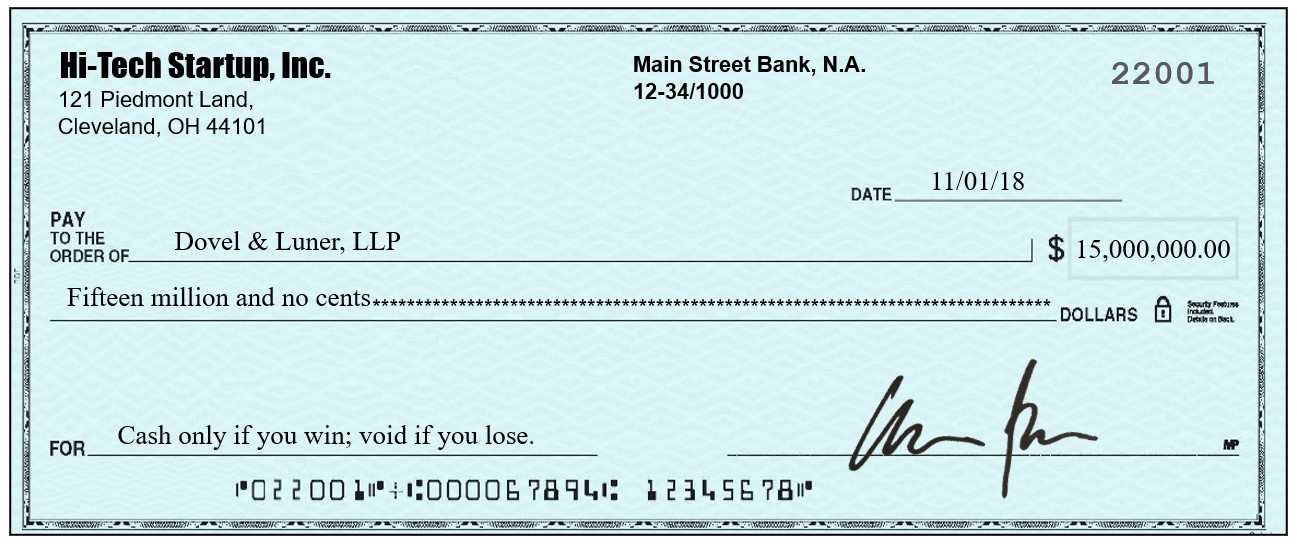

Now consider two teams of lawyers hired to litigate a $50 million business dispute. The two teams have the same number of lawyers with identical experience and skill. They differ in only one way—compensation. The first legal team bills per hour. The team provides an estimated budget of $12 million to litigate the case—but will not be held to that estimate. Whether this team wins or loses does not affect how much the team bills and correspondingly how much it makes. If the team wins, it gets whatever it bills; if it loses, it gets whatever it bills.

The first team’s direct economic incentive is to bill hours. The firm’s billers keep track of their time in increments such as tenths of an hour. The more time increments the firm bills, the more the firm makes. This legal team has essentially no skin in the game.

The second legal team gets paid for results. They get $15 million if they win, $0 if they lose. The following figurative check illustrates this type of conditional payment: “Cash only if you win, void if you lose:”

Which legal team is more likely to have the gumption, drive, and creativity to win? Which legal team will be up at night concerned about potential problems with the case, and developing ways to solve them? “[L]inking the attorney’s fees to the trial’s outcome induces the attorney to exert a higher … effort than could be implemented using hourly or fixed fees.” 29

“An incentive is a bullet, a key: an often-tiny object with astonishing power to change a situation.”

Steven D. Levitt

As the second team struggles through the challenges inevitable in high-stakes litigation, these lawyers know that if they don’t win, they don’t get paid. This team has skin in the game.

B. A downside survival risk is a profound motivator that produces even

better results.

Returning to the CEOs, assume that the base salary of the incentivized CEO is not $5 million; it is $0. Her entire compensation consists of pay-for-performance incentives. If the company does not hit the target milestones, she gets nothing. Without a guaranteed salary, she will be even more driven to ensure that the company hits its milestones.

Now let’s add another twist: if the company does not hit the target milestones, the CEO has to pay the company $2 million cash out of her own pocket. By sharing disincentives, her own economic survival depends on the company’s success.

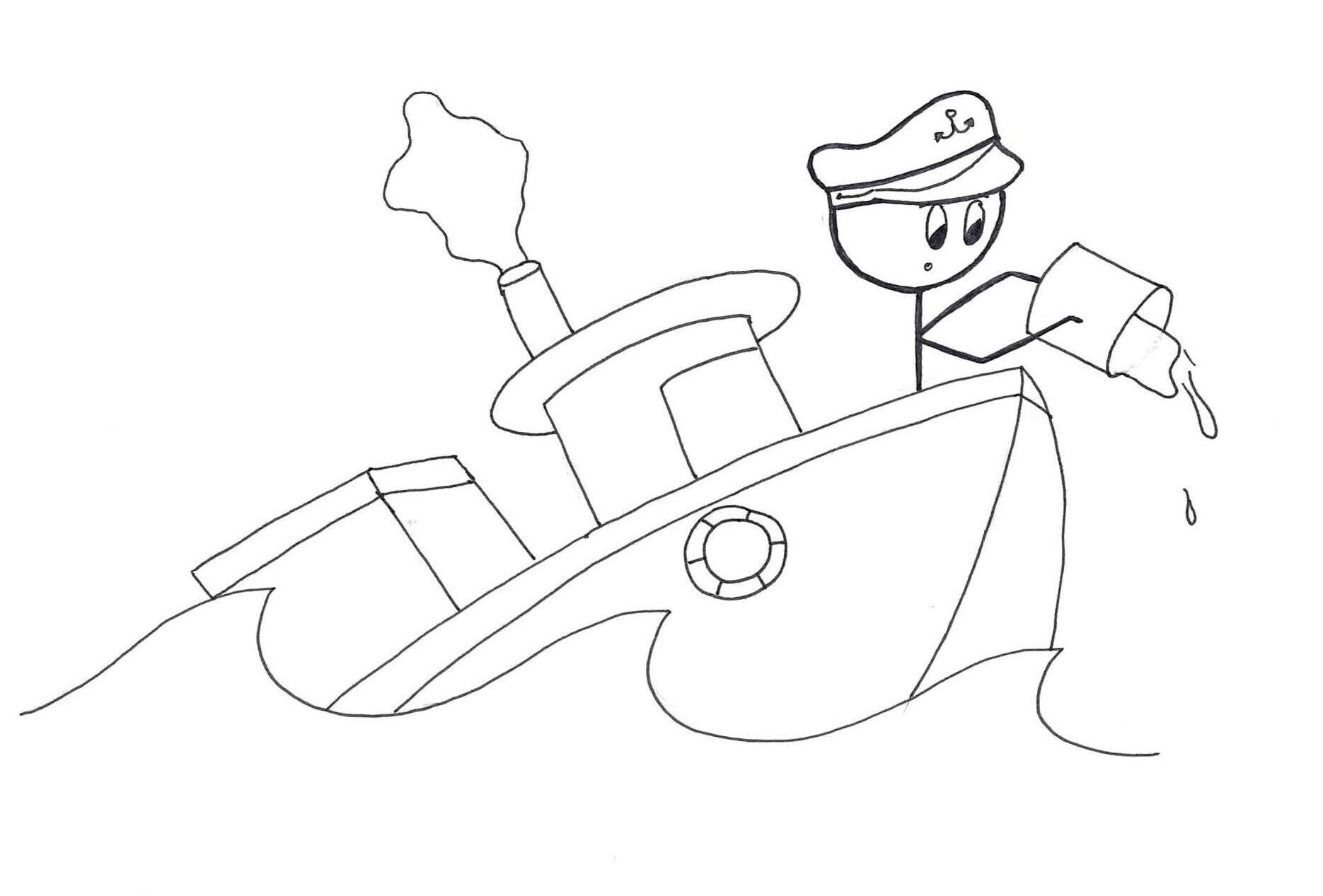

Pay-for-performance incentives work. But real skin in the game requires an even more powerful driving force—the will to survive. The captain who risks going down with the ship will be profoundly more motivated to keep her ship afloat than the captain who can paddle a life boat to safety at the first sign of a leak.

Similarly, a high-stakes contingency fee firm that not only risks its time, but also its own cash, has real skin in the game. If this firm does not win, the partners must draw millions in litigation costs out of their own capital accounts.

Having this real skin in the game creates a profound motivation to dig deeper when it is most difficult—the firm’s survival depends on it.

V. Conclusion

Hiring a contingency fee law firm to litigate a high-stakes case eliminates the downside risk of paying millions in attorneys’ fees and costs and results in critical client benefits.

^ 1 Emons, Winand, Conditional Versus Contingent Fees, Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 59, no. 1, 92, 246 note 7 (2007).

^ 3 Virginia G. Maurer, Robert E. Thomas, & Pamela A. DeBooth, Attorney Fee Arrangements: The U.S. and Western Perspectives, 19 Nw. J. Intl. L & Bus, 272, 290 (1999).

^ 4 Other client considerations are obtaining nonmonetary relief, minimizing management’s distraction and impact, public relations, and regulatory and financial market impact.

^ 5 David Schwartz, The Rise of Contingent Fee Representation in Patent Litigation, 64 Alabama Law Review 335, 336 (2012).

^ 6 Gross, Samuel R., We Could Pass a Law…What Might Happen if Contingent Legal Fees Were Banned, DePaul L. Rev. 47, no. 2, 336 (1998).

^ 7 Virginia G. Maurer, Robert E. Thomas, & Pamela A. DeBooth, Attorney Fee Arrangements: The U.S. and Western Perspectives, 19 Nw. J. Int’l L. & Bus. 272, 293-94 (1999).

^ 8 Helland & Tabarrok, Contingency Fees, Settlement Delay and Low-Quality Litigation: Empirical Evidence from Two Datasets, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Volume 19, Issue 2, 517-542 (2003).

^ 9 Helland & Tabarrok, Contingency Fees, Settlement Delay and Low-Quality Litigation: Empirical Evidence from Two Datasets, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Volume 19, Issue 2, 517-542 (2003).

^ 10 Ravdin, Linda J. and Capps, Kelly J., Alternative Pricing of Legal Services in a Domestic Relations Practice: Choices and Ethical Considerations, Family Law Quarterly 33, no. 2 387, 289 note 14 (1999).

^ 11 Ravdin, Linda J. and Capps, Kelly J., Alternative Pricing of Legal Services in a Domestic Relations Practice: Choices and Ethical Considerations, Family Law Quarterly 33, no. 2 387, 391 (1999).

^ 12 Ross, The Ethics of Hourly Billing By Attorneys, Rutgers L. Rev. 44 No. 1 1, 2-3 (1991); Alexander Tabarrok and Eric Helland, Two Cheers for Contingent Fees, American Enterprise Institute (2005) (“It is difficult for a plaintiff to evaluate how much effort a lawyer puts into a case. Timesheets are not easily verifiable, and even if they were, hours are not the same as effort.”); “The billable hour inherently ‘encourages firms to overstaff matters, lard their bills with marginally useful services, and draw out cases that might be brought to a swifter conclusion.’” In re AOL Time Warner, Inc. Sec. & “ERISA” Litig., 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 78101, at *23 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 28, 2006) (quoting Douglas McCollam, The Billable Hour: Are Its Days Numbered? 183 N.J.L.J. 285, 286 (Jan. 30, 2006)).

^ 13 Emons, Expertise, contingent fees, and insufficient attorney effort, International Review of Law and Economics, 22 (2000).

^ 14 Gordon & Rapoport, Virtuous Billing, 698, (Spring 2015).

^ 15 David Schwartz, The Rise of Contingent Fee Representation in Patent Litigation, 64 Alabama Law Review 335, 336 (2012).

^ 17 For example, clients have brought lawsuits against their attorneys accusing the attorneys of “deceptive billing practices” including block billing (“often utilized by large law firms to pad the hours actually worked on a matter and drive up amounts billed to clients”), hoarding (“when an overqualified service provider with a high billing rate retains work rather than passing it onto a service provider equally capable of doing the work, but due to experience level, has a lower billing rate” and “multi-billing” (“when multiple attorneys are tasked with performing the same task or to attend the same event when the weight of the work can realistically be handled by only one attorney.”) Complaint, 1:20-cv-00112-CMR, (August 2020 District Court Utah).

^ 18 Michael A. Dover, Contingent Percentage Fees: An Economic Analysis, 51 J. Air L. & Com. 531, 554-55 (1986); Gross, Samuel R., We Could Pass a Law…What Might Happen if Contingent Legal Fees Were Banned, DePaul L. Rev. 47, no 2, 336 (1998).

^ 19 Ravdin, Linda J. and Capps, Kelly J., Alternative Pricing of Legal Services in a Domestic Relations Practice: Choices and Ethical Considerations, Family Law Quarterly 33, no. 2 387, 389-390 (1999).

^ 20 Helland & Tabarrok, Contingency Fees, Settlement Delay and Low-Quality Litigation: Empirical Evidence from Two Datasets, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Volume 19, Issue 2, 517, 518 (2003).

^ 21 Dana & Spier, Expertise and Contingent Fees: The Role of Asymmetric Information in Attorney Compensation, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 350 (1993).

^ 22 Emons, Winand, Conditional versus Contingent Fees, Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 59, no. 1, 92 note 6 (2007).

^ 23 Altman, Adam, To bill or Not to Bill?: Lawyers Who Wear Watches Almost Always Do, although Ethical Lawyers Actually Think About It First, 11 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 203, 203 (1998).

^ 24 Ross, The Ethics of Hourly Billing by Attorneys, Rutgers L. Rev. 44 No. 1 1, 3 (1991).

^ 25 David Schwartz, The Rise of Contingent Fee Representation in Patent Litigation, 64 Alabama Law Review 335, 336 (2012).

^ 26 Helland & Tabarrok, Contingency Fees, Settlement Delay and Low-Quality Litigation: Empirical Evidence from Two Datasets, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Volume 19, Issue 2, Abstract (2003).

^ 27 Moorhead, Richard, An American Future? Contingency Fees, Claims Explosions and Evidence from Employment Tribunals, The Modern Law Review 73, no. 5 763 note 2 (2010).

^ 28 Lilinfeld-Toal, U.V. & Ruenzi, S., CEO Ownership, Stock Market Performance, and Managerial Discretion, The Journal of Finance, 69, 1013-1050 (2014).

^ 29 Dana & Spier, Expertise and Contingent Fees: The Role of Asymmetric Information in Attorney Compensation, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 350 (1993).