Ethos: the lawyer’s character

I am in the midst of writing a book explaining the 20 principles of human persuasion for trial lawyers. It includes a chapter on ethos, which is presented below. I hope you enjoy.

–Greg Dovel

A. Why ethos matters

Twenty-four centuries ago, Aristotle identified an advocate’s “ethos,” or moral character, as one of the key forces of persuasion. Aristotle, On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse 1.2.2 (Kennedy ed. 1991).

And today all trial lawyers have some understanding that their own persona (i.e. what jurors perceive the lawyer’s character to be) is a tool of persuasion.

Renowned trial lawyer Herb Stern offers the following analysis of why an advocate’s perceived character matters:

Herbert J. Stern, Trying Cases to Win, 13, 15 (1991)

People make some decisions simply because they trust the source of the argument, without processing whether the argument is itself persuasive. Moreover, the perceived trustworthiness of a lawyer influences decisions even when a juror is actively and skeptically engaged in cognitive processing trying to figure out which arguments make the most sense.

For example, a lawyer in closing argument says:

“The defendant claimed that the money my client invested in the company was spent on hiring engineers to develop new products. That was a lie. His own business partner admitted on the stand that they didn’t hire a single engineer or develop a single new product. The defendant simply took my client’s money and pocketed it.”

A juror’s perception of the lawyer determines whether the juror accepts or doubts the assertions in this argument. Did the defendant’s partner really testify that the company didn’t hire any engineers or develop any new products? In the example above, the lawyer did not show the juror the business partner’s actual testimony. And the juror may not sufficiently recall the testimony on this point if it was not clear, memorable, and of obvious relevance at the time it was presented. Whether the juror believes that testimony was given could depend largely on the lawyer’s credibility.

But what if the lawyer had read to the jury from the actual transcript containing the business partner’s admission? If the lawyer were perceived as trustworthy, that may suffice to remove all doubts. But if a juror perceives the lawyer as sneaky and untrustworthy, the juror may actively look for sources of doubt: was the lawyer accurately reading the testimony, taking it out of context, or failing to mention other testimony that would put quoted testimony in a different light? The more the lawyer is distrusted, the more those doubts are magnified.

The lawyer touches, or appears to touch, every line of testimony, document, and argument in the case. The lawyer, therefore, has the perceived power to distort, spin, or pollute every building block that leads to a decision. For that reason, the lawyer’s ethos has a pervasive influence on a juror’s decision-making.

B. The ethos of the guide

The best advocate is someone who does not appear to be advocating—the non-advocate. By contrast, the archetype of the persona that does not persuade is the used car salesperson.

People do not like or trust the stereotypical used car salesperson. The hard sell results in sales resistance. When pushed, people push back. This is the opposite of the desired result.

The advocate with an ethos that persuades avoids everything that says “salesperson.” Instead, he or she becomes a trusted guide. A useful archetype may be a respected teacher or professor, someone who really cared about the subject being taught and about the students. This is the professor who was more excited about finding truth than about satisfying his own ego.

All of the positive personal qualities that make someone well-liked can be useful for persuasion, including qualities such as being polite, respectful, humorous, or dignified. Certain qualities, however, are essential to (i.e. the essence of) a persuasive ethos.

Imagine that you sat as a juror on a case and by the end of the trial had the firm impression that the lawyer representing the plaintiff was fastidiously honest and was also a self-centered son-of-a-bitch. You also had the firm impression that defense counsel was extremely nice, polite, charming, and funny, but was willing to lie about anything. Which lawyer’s closing argument would have greater persuasive power for you?

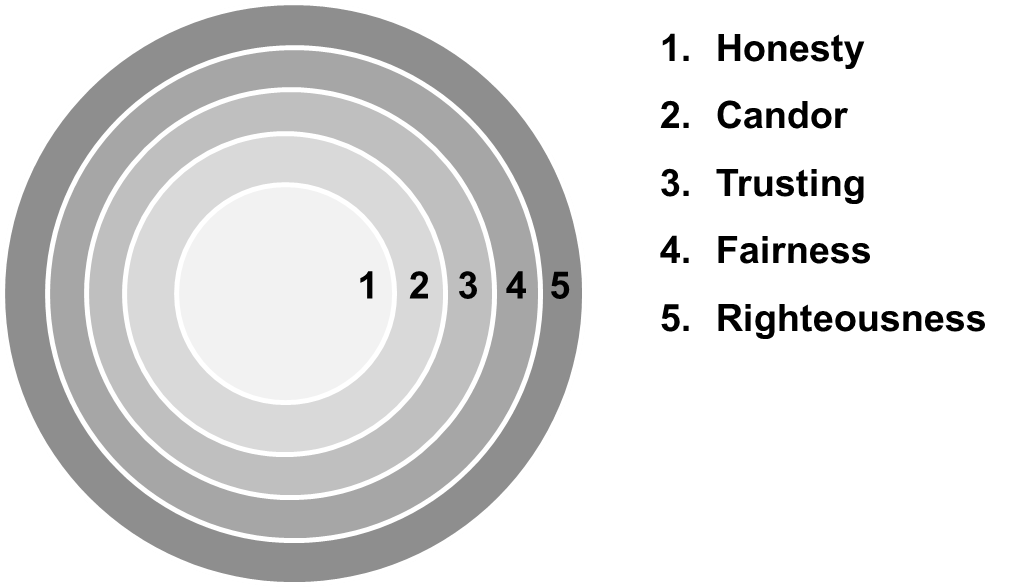

The ideal persona for persuasion (the ethos that persuades) has five components.

1. Honesty

You speak the truth. You do not overstate or mislead or unfairly characterize. You elicit the truth rather than spin the facts.

2. Candor

You are authentic, transparent, and do not conceal anything about your client, your case, or (most importantly) yourself. Reality comes with blemishes; you present the truth, warts and all.

3. Trusting (this is the converse of trustworthiness)

Although you participate in the journey as a helpful advisor, you trust the jurors to reach the right decision. You are not pushing or selling anything.

4. Fairness

You think fair play is as important as winning. You do not have a personal interest in a particular party winning. At the start of the trial, you are just like the jurors: neutral. You desire a fair and just result more than a result that favors your client.

5. Righteousness

You have a visceral response to injustice and are passionate that justice should prevail.

Righteousness will sometimes conflict with fairness and with trusting the jury. How can you want to be fair to both sides and to let the jury make the decision, yet care deeply that the right side (your side) wins? The key is to strike the right balance at the right time. Take the journey with the jury. At the very beginning you are neutral and fair to both sides. Over time, the jury will become more confident that your side is the right side. In final argument, choose a few moments to advocate passionately the righteousness of your side.

Synonyms and antonyms for the proper ethos:

- The advocate with the proper ethos is honest, straight, upright, honorable, impartial, principled, incorruptible, trustworthy, candid, artless, guileless, natural, naïve, sincere, authentic, and frank.

- The advocate cares about integrity, truth, justice, probity, rectitude, good faith, fairness, fair play, equity, and veracity.

- The advocate avoids all that is slick, tricky, crooked, wily, crafty, sly, cunning, devious, deceptive, overreaching, shifty, phony, and artificial.

C. To present an ethos you must have that ethos

After realizing that ethos is important to persuasion, some advocates work on correcting aspects of their persona, of how they appear to others. That focus is a mistake—it attempts to fix one or two symptoms rather than curing the disease. You must have the character of the guide, not simply attempt to put on the persona of the guide. The following provides some specific ways to both have and present the proper ethos.

Be yourself

Christin Cho – direct examination

An audience quickly smells out someone who is not authentic, who is putting on a personality that does not come from within. What appears on the outside must reflect the inside, or it will be perceived as an act, as an attempt to display something that is not true. And, of course, if a juror perceives a lawyer as false, the lawyer has achieved precisely the wrong result.

This is one of the points where acting and advocacy mesh.

Bad acting. We know we are watching a bad actor when we can see the acting. The actor tries a little too hard, smiles a little too much, and laughs a little too loud. We see emotion because the actor is purposely emoting. The actor is putting on a role, playing make-believe.

Good acting. The good actor does not wear a role; the good actor embodies the role. The Bravo channel series “Inside the Actor’s Studio” presents our greatest living actors describing their craft. Invariably, they point to their efforts to avoid acting, to avoid artifice. They talk of “being in the moment,” of not thinking, of being surprised, of really listening to the other actors.

Acting is believing. The emotion we see comes from inside. To convey sadness, the bad actor puts on loud sobbing and anguished facial expressions. The good actor feels the emotion but then holds it in, minimizing expression of the sadness. The audience sees the emotion in the actor’s genuine effort to avoid sobbing.

Live what you seek to convey

Julien Adams – direct examination

We know (1) you must be yourself, and (2) your ethos must convey the persona of a guide (honest, candid, trusting, fair, and righteous). The only way to accomplish both of these goals is for you to make these attributes a habit, not an act.

You cannot convey an ethos through artificial means. To present ethos you must have ethos.

To have the best chance of conveying honesty, candor, and fair play you must embody those things in the courtroom. To have the best chance of embodying honesty, candor, and fair play in the courtroom, you must have those traits as reflexes. To become reflexes, they must be adopted as habits in your daily life.

Build and present an honest case

To convey that you care about truth and fair play above all else while simultaneously advocating your clients’ position requires that you actually be unafraid of any evidence or witness, totally believe in your client’s case, and entirely trust the jury to make the right decision.

To believe in your client’s case requires that you do two things. First, you must fully investigate and analyze the evidence so that you know what is true. Second, you must adopt a theory of the case that incorporates all the believable evidence. The most common source of problems for a lawyer’s ethos is that the lawyer tries to make his case a little too perfect, or a little more favorable than it really is. He presents a case that includes statements and positions that the jury will disbelieve.

If your case is built around the truth after a thorough investigation, you will not fear any argument or evidence. The opposing argument and evidence will necessarily be incorrect, and you will have an answer to rebut it. You can be candid, fair, and trust the jury.

Be authentic and transparent

Honesty and candor are related, but candor is not just a modest addition to truth. Candor is truth to the second power.

Candor always requires truth, but not all truths require candor. Candor can exist only when you are presenting a truth that you do not want to disclose.

You are not being candid when you present a true fact that helps your case. You are candid when you present a true fact that undermines your case.

I am not being candid when I truthfully tell you about a highlight of my career. I am candid when I disclose one of my screw ups. I am not being candid when I tell you about my act of kindness in helping a stranger. I am candid when I tell you about a time I was a selfish coward.

There is no such thing as being candid about something that makes you, your client, or your case look good. Candor always produces discomfort.

You will have to be candid about your case. You will have to tell jurors about evidence and arguments that the opposing lawyer really likes. However, being candid about your case is actually pretty easy. It mostly requires adjusting your theory of the case to accommodate all of the facts that the jury is likely to believe.

You will also have to be candid about your client, which is a little harder. You will have to disclose the unlikable parts of your client’s personality and past.

The hardest of all is that you will have to be candid about yourself. You are not going to show up at court with your “interview” self, the one you take to a job interview. You are not going to show up as your “trial lawyer” self—the smart, articulate, polished persona that steps up to the lectern to give a rehearsed argument. You are going to have to be your authentic self.

Greg Dovel – voir dire

To be authentic, you are going to have to be vulnerable. As legendary trial consultant Josh Karton puts it: “A lawyer must allow himself to be seen, unprotected.” That is going to feel uncomfortable.

Knowing that candor is not going to feel good, then why be authentic and transparent, why show yourself to the jury? When properly wielded in a courtroom, authenticity is a superpower. If I were to pick one attribute, skill, or bundle of knowledge to give a lawyer that would do the most to improve their power to persuade in a courtroom it would be authenticity.

I am a graduate of Gerry Spence’s Trial Lawyer’s College. The core of the TLC method is personal authenticity. And Spence’s greatest gift to advocates was in showing the power of authenticity. Spence won a number of difficult cases (representing both plaintiffs and criminal defendants) largely, I believe, as the result of authenticity. In recent years, TLC graduate Nick Rowley has taken that learning to a new level, and the result has been a string of eight-figure verdicts.

Why does authenticity work so well in a courtroom? Part of it is easy to understand, and part of it is still a mystery.

Candor or vulnerability are not merely intellectual attitudes. Candor comes with emotional discomfort. Vulnerability comes with feelings. When a lawyer is candid and vulnerable the resulting feelings show up in the lawyer’s voice pattern, posture, and gestures. By the time we reach adulthood, we have all seen and heard these physical patterns a hundred times, and our intuitive mind (what cognitive psychologists call “System 1”) is highly trained to recognize them. As a result, candor and authenticity instantaneously communicate to a juror’s System 1 mind that this lawyer is not hiding or holding back the truth. Repeated displays of authenticity by a lawyer teach a juror’s System 1 (intuitive mind) that this lawyer can be trusted. And that juror’s subconscious trust in the lawyer then enhances the believability of every piece of evidence and argument the lawyer touches.

But a lawyer’s authenticity evokes another response in jurors that may be of equal importance to trust. When a lawyer allows herself to be seen, jurors connect with the lawyer. I have heard many people describe this feeling of connection. And I have felt it myself (both as advocate and as audience member), so I know it is real. But I don’t yet have any meaningful understanding about why or how this happens.

With that feeling of connection comes something that goes beyond a juror trusting the lawyer. It seems to include as a component that the juror wants to support and help the lawyer. It is as if the lawyer and juror were on the same team, or were part of the same clan or tribe. Such a connection does not guarantee that the juror will vote for the lawyer’s client during jury deliberations. But if the juror is persuaded, then when deliberations begin, the connected juror may have a greater willingness to advocate forcefully.

Cultivate the opposing lawyer’s trust

You want the opposing lawyer to convey to the jury that you are trustworthy. All of the subtle messages that the opponent delivers to the juror about you should say, “You should trust this guy, because I do.”

To accomplish this, the other lawyer must believe you are trustworthy. To instill that belief in your opponent, be trustworthy. Be the kind of lawyer whose word can be trusted. Be the kind of lawyer who attempts to win on the merits.

For example, when discussing discovery obligations, if your opponent makes a good argument that causes you to change your position, then freely acknowledge it and give that position away.

Distrust the opposing lawyer

If you are a helpful guide and represent the truth, your opponent is a paid salesman who advocates a lie. Your attitude toward your opponent is courteous and respectful but also distant.

Why courteous? The message is, “I believe in fair play. There is nothing about this lawyer or his presentation that I want to hide from you. I have no reason to unfairly deny him an opportunity to present his case, because when you see his case, you will see it is weak.” Among other ways, you will demonstrate this at trial by assisting your opponent when technical snags arise with courtroom technology, with locating physical documents, and by limiting your objections.

Why distant? You must also convey to the jurors that the opposing lawyer is not trustworthy. To convey your belief that the other lawyer is untrustworthy, you must believe it. Your courtesy in assisting the other lawyer does not go so far as to be friendly. In front of the jury, you do not smile at the opponent, do not make jokes with the opponent, and do not leave the courtroom together.

Jurors will not trust you as an honest guide if they see you as a hired gun playing a game; someone who purports to be distant from the opponent while the game is underway, but then turns around and starts trading war stories over beers with the opponent once the whistle blows. You must care enough about the truth of your client’s position (i.e., your position) that you are truly offended by the false accusations your opponent makes.

D. The balance between ethos and advocacy

Two seemingly contradictory goals are present at every turn. On the one hand, the lawyer must maintain his ethos—he must appear to be the guide and not the advocate. On the other hand, the lawyer must make strong arguments and deliver deep blows for his points to have impact.

You must balance these competing goals to maximize persuasion. This is a bit like the tension between preservation of capital and using capital. One saves money so that one can spend it later. If money is spent now, it is gone, and cannot be used later. On the other hand, money never spent is worthless.

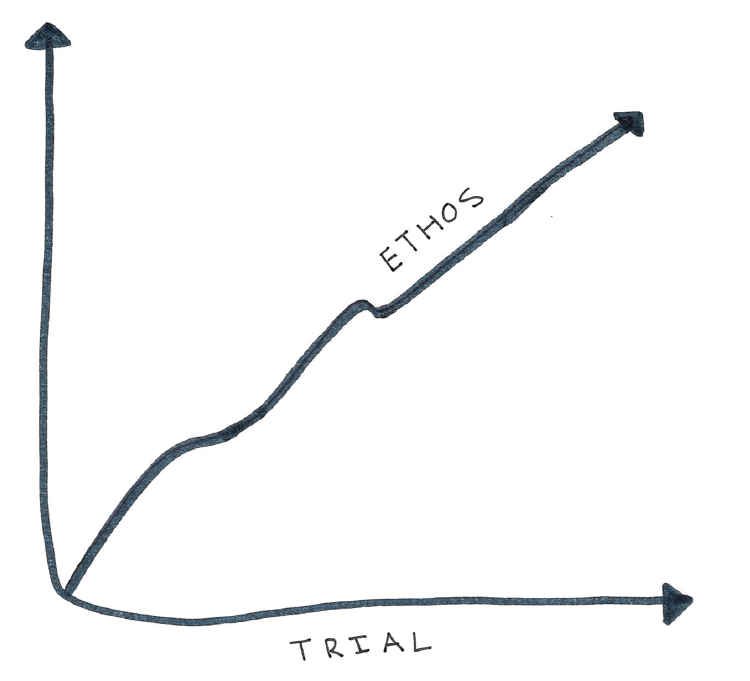

Your ethos is earned over time with a jury. It is the culmination of 100 nuances that say, “This person is trustworthy. This is a good and decent person. This is not a lawyer trying to deceive me.”

For the most part, you will be preserving and building your personal capital with the jury. You do not deliver deep blows yourself; thrusting, jabbing, pulling along, advocating. Instead, you allow something else to deliver those blows: evidence.

Think of yourself as someone who simply arranges raw materials. You arrange raw materials (documents, testimony) in a manner that compels your conclusion. Then you step back and allow the audience to make up its own mind. You develop evidence and arguments that are deep and powerful even when delivered softly.

During the course of the trial, at one or two vital moments, you may have to spend some capital. Then, in final argument, you can spend most (but not all) of your remaining capital. In the jury room, you want the jurors to continue to think of you as having a credible ethos. Another way to think of it is that credibility is like water pressure. You build it up to use on a key point. But when you use it, don’t empty the tank and run the water pressure down to zero. In closing argument you assert strong pressure and then ease off before the tank is empty.

E. Ethos at the opening of the trial

Ethos is at its most fragile during jury selection and voir dire. At this stage, a lawyer’s ethos bank account has no deposits. In fact, by virtue of being a lawyer, the lawyer starts with an ethos deficit: you are distrusted. For this reason, it is not enough to merely protect ethos in voir dire. You should go further and do everything you can to grow ethos.

The dynamics of ethos resembles the dynamics of compound interest. The sooner and faster you start growing positive ethos, the larger the impact will be later on.

The lawyer needs a large store of ethos for later phases, such as closing argument, and perhaps for other stages as well, such as cross-examination of the opposing party, or dealing with a nasty surprise. It is even useful to have a small supply of positive ethos as soon as opening statement. It is crucial, therefore, to maximize positive ethos during voir dire. Indeed, that is the primary purpose of voir dire, and all other purposes (including advocacy and weeding out bad jurors) become secondary.

I describe elsewhere specific techniques to use during voir dire that will grow your credibility bank account. In general, for most of your voir dire it should be difficult to determine which side you are representing. For example, if a juror discloses an obvious bias against the opposing party and can be challenged for cause, don’t wait for your opponent to do it. Instead, explore that with the juror. “Since you feel like you are already leaning against the defendant, do you think it might be better if you were a juror on a different case? I believe in fair play, so would you mind if I asked the judge whether you could be excused from this case?”

During opening statement, you also need to preserve and continue to build ethos, particularly during the first few minutes of the opening. Avoid the adjectives and adverbs, the purple prose and cheesy rhetoric. The advocacy should come from factual details that move the story forward and using evidence in as raw a form as possible to take advantage of what we call “the Mona Lisa effect.”

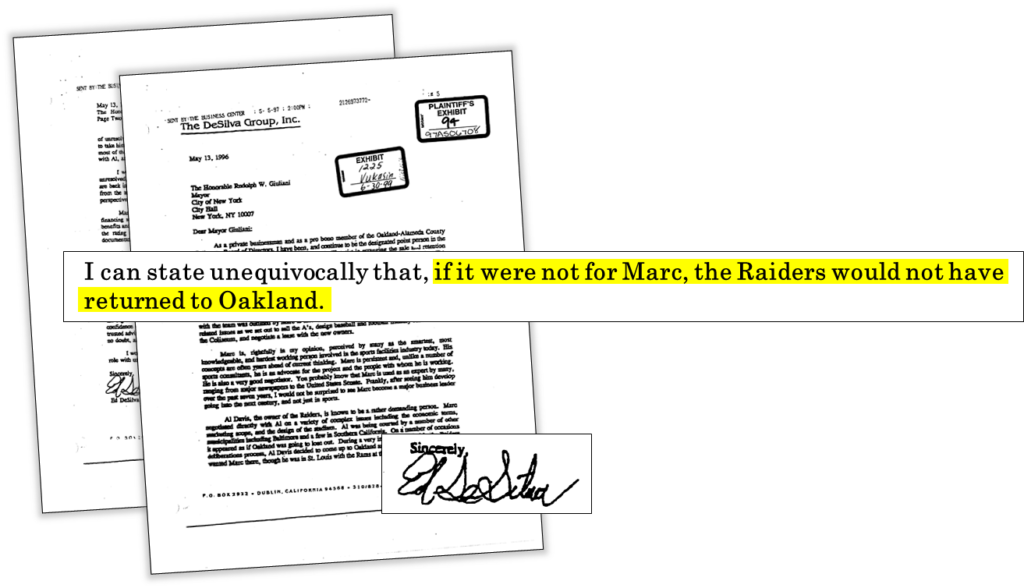

Evidence is more persuasive in opening statement to the extent it is as close to the original as possible, allowing the audience to make up its own mind. An example is displaying a letter signed by the opposing party containing a damaging admission in plain language.

Even a statement backed up by a cite to a witness (Mr. X, who is credible because of __, will testify as follows __) is better than an advocate’s bald assertion.

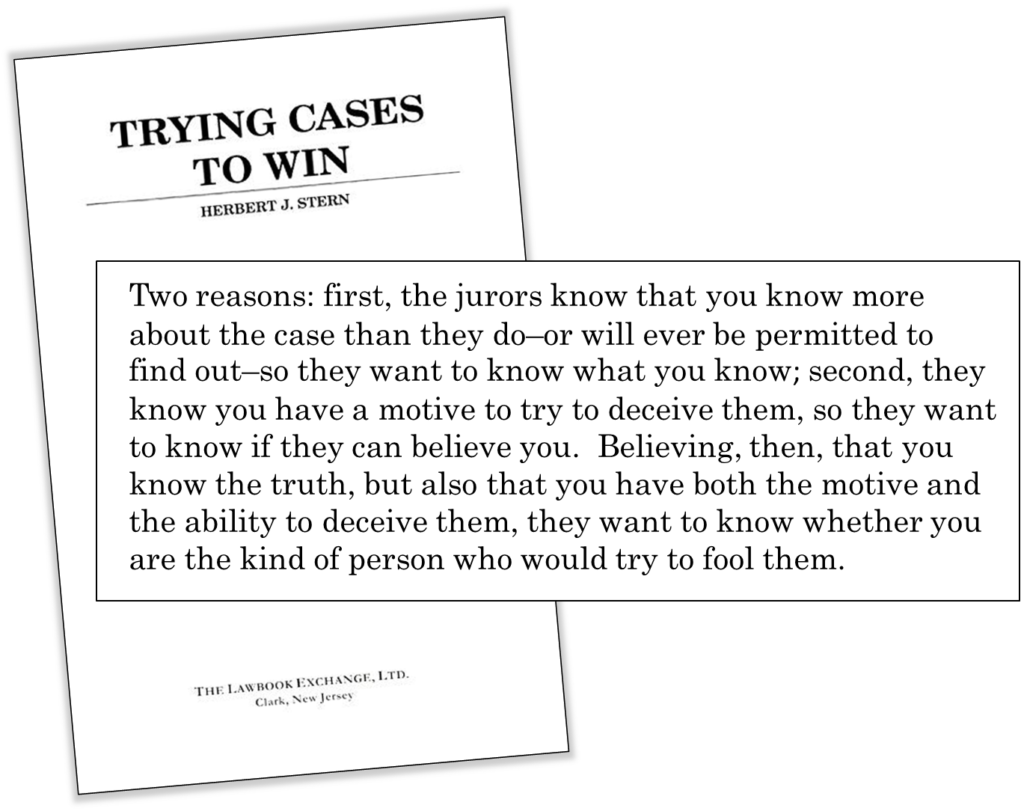

Presenting deposition admissions in opening statement

When using key deposition admissions in opening statement, present them in the form of a direct quote from the witness as if it were actual testimony. This requires three components.

First, you must actually read the testimony. If you are not looking at a document when you present it, then it is coming from your mind, not from the document. If it is coming from your mind, then there is the potential that you are making it up or misremembering it.

Second, if allowed, display the relevant portion of the transcript on the screen. If not allowed, then read from an actual bound transcript that you hold in your hands. In other words, do not merely read from your opening statement notes, or from a note card. You must actually reach over and grab something that looks official and weighty.

Third, you must read it word for word, including “Question,” “Answer,” as well as the awkward pauses or phrasing. The goal is for the jury unquestionably to believe that what you are reading is the actual sworn testimony.

“I will prove” versus “The evidence will show” in opening statement

The brilliant trial lawyer Herb Stern contends that trial lawyers, in opening statement, should always use (and frequently repeat) the phrase that contains the strongest personal commitment: “I will prove to you that…” Stern favors this over language such as “the evidence will show that…” Stern reasons that putting the advocate’s personal ethos behind each statement gives the statements greater believability at the critical juncture of opening statement. This is bad advice.

Asserting “I will prove to you…” undermines ethos. The epitome of the hard sell is the salesman stating, without proof, “buy this, trust me, it is great.” The opposite of the hard sell is having jurors discover, on their own, evidence that persuades them with no comment from the lawyer. A lawyer (i.e., professional salesman) stating, “I will prove” closely matches the hard sell. It is at the opposite end of the spectrum from hard evidence.

By contrast, stating “the evidence will show” is doing what the ideal persuader should do: have a case so strong that the evidence will lead jurors.

Stern’s analysis confuses the need for confidence with the need for personal advocacy. The advocate must not be tentative or imply that she is uncertain about the evidence or the truth of the facts asserted. Lack of confidence suggests to the jury that the lawyer knows the truth and knows that what she is saying is not true. But confidence is conveyed through tone of voice, and by avoiding tentative language (such as “I think the evidence will likely show,” “if I misstate anything, I apologize,” etc.). Confidence does not require “I will prove to you…”

F. Effective not aggressive

When clients enter litigation, the character trait they most often seek is: “I’m looking for an aggressive litigator.” They want the bulldog, the tiger, the shark, the killer. They think that they want the nasty lawyer with a loud bark.

But clients are mistaken when they focus on bark. A loud bark merely irritates. Sharp teeth inflict pain.

A loud bark rarely gets a client a great result. And it often winds up costing the client more money, time, and aggravation.

Jeff Eichmann – cross-examination

What clients really want is effectiveness.

They want a lawyer who will state a firm position, and then back it up with action that devastates the other side. It takes effective action to alter behavior and change attitudes. And that is what a client actually wants.